This month, Talking Science delves a little deeper into the science behind coral bleaching and shares some early insights into this year’s spawning event.

BACKGROUND ON BLEACHING

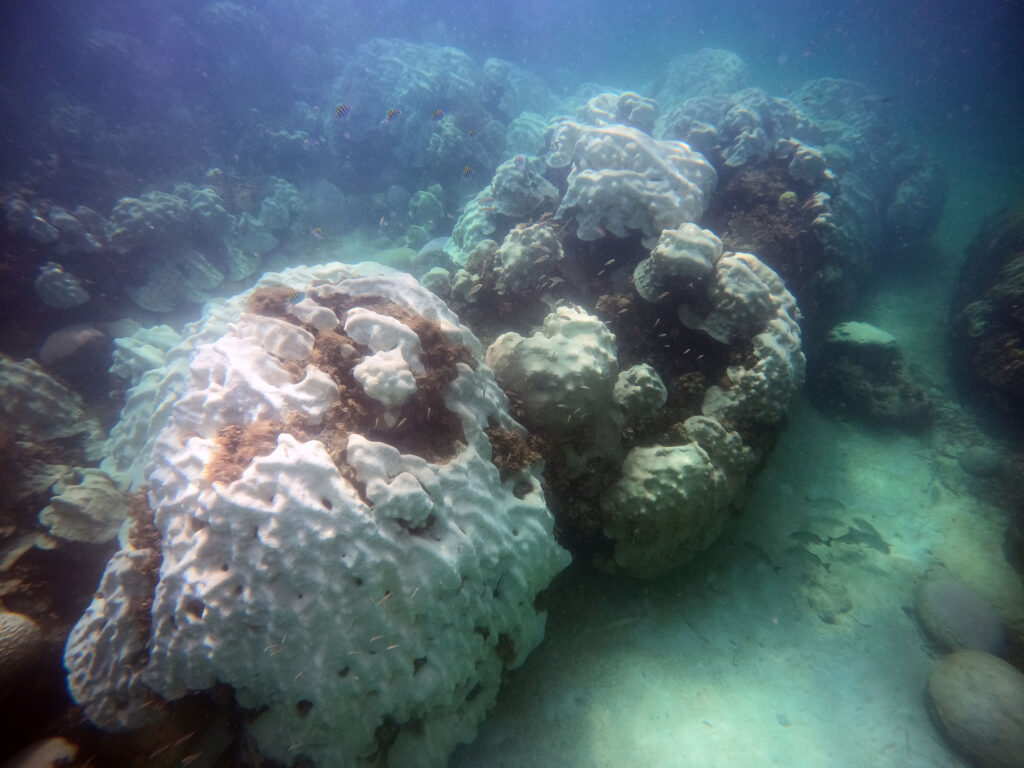

Corals are unique animals that have formed a mutualistic relationship with a special single-celled algae called zooxanthellae. The zooxanthellae live within the tissue of the coral polyps, making the coral appear colorful. While the algae get a protective home and carbon dioxide from the coral’s respiration, the coral gets the excess sugars (food) and oxygen produced by the zooxanthellae’s photosynthesis. This relationship has resulted in the survival of coral reefs in the tropical zones of the planet.

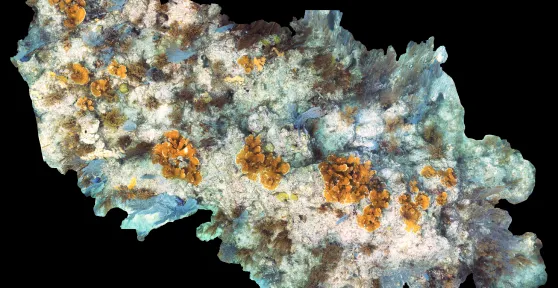

This mutualistic relationship is a delicate balance of give and take. However, this relationship can break down. For reasons not fully understood, the coral will kick out the zooxanthellae when they experience stressful conditions, including warm water events. Without their colorful friends, the white skeleton shows through the clear coral tissue. This state is called coral bleaching and puts the coral colony at risk as it is no longer getting enough energy to survive. Scientists measure warm water events using the sea surface temperatures viewed by satellites. By comparing the water temperature to historical values, scientists can predict the duration and severity of bleaching events using degree heating weeks. A degree heating week is a measurement used to communicate potential bleaching responses in coral reefs when the average water temperature is equal to or greater than 1°C above of the monthly historical average. Unfortunately, bleaching events are becoming a recurring global issue instead of a localized or regional response. Global bleaching is predicted to affect all reefs on the planet in the very near future.

Fortunately, some reefs, individual corals, and genotypes do experience less bleaching severity. Before this year, the best example of this from the Florida Keys was at Cheeca Rocks, an inshore patch reef in Islamorada. The Florida Keys experienced mass bleaching events in 2014 and 2015. In 2014, the warm water event had a 7.7-degree heating week value and resulted in 38% of corals becoming fully bleached and 36.6% paled or partially bleached. The event in 2015 was warmer still with a 9.5 degree heating week value. However, the corals experienced less bleaching, only 12.1%. While the corals did become stressed, they recovered well and had a 94.7% survivorship from 2014 to 2016. While the water was warmer for longer in 2015, the corals may have acclimatized from their experience in 2014, demonstrating that although back-to-back bleaching events can be difficult, corals are adaptable and resilient and given enough recovery time between bleaching events, mortality may continue to be low in certain areas.

This year’s bleaching event, however, is proving to be more than many of even our hardiest corals can cope with. Cheeca Rocks has experiencee almost total bleaching and widespread mortality already. Sombrero, Newfound Harbor, Eastern Dry Rocks, and Looe Key have also succumbed to the heat.

A number of reefs in the Upper Keys are still holding out, however, which is encouraging, and many of the corals in our Carysfort and Tavernier Coral Tree Nurseries are also doing well. Unfortunately, we are still looking ahead at elevated water temperatures for several weeks to come.

Stay connected with CRF™ on social media for ongoing updates.

_________________________________________________________________________________________

SPAWNING WARNINGS

Every year in August at night after the full moon, Acroporid corals (staghorn and elkhorn) spawn.

Different species of corals spawn at different times and in a few different ways. Staghorn and elkhorn are hermaphroditic broadcast spawners, meaning that each polyp releases both types of gametes, eggs and sperm, in a bundle that floats to the water’s surface. The bundles break apart and gametes from different colonies and fertilize to generate the next generation of corals for the Florida Keys reef system.

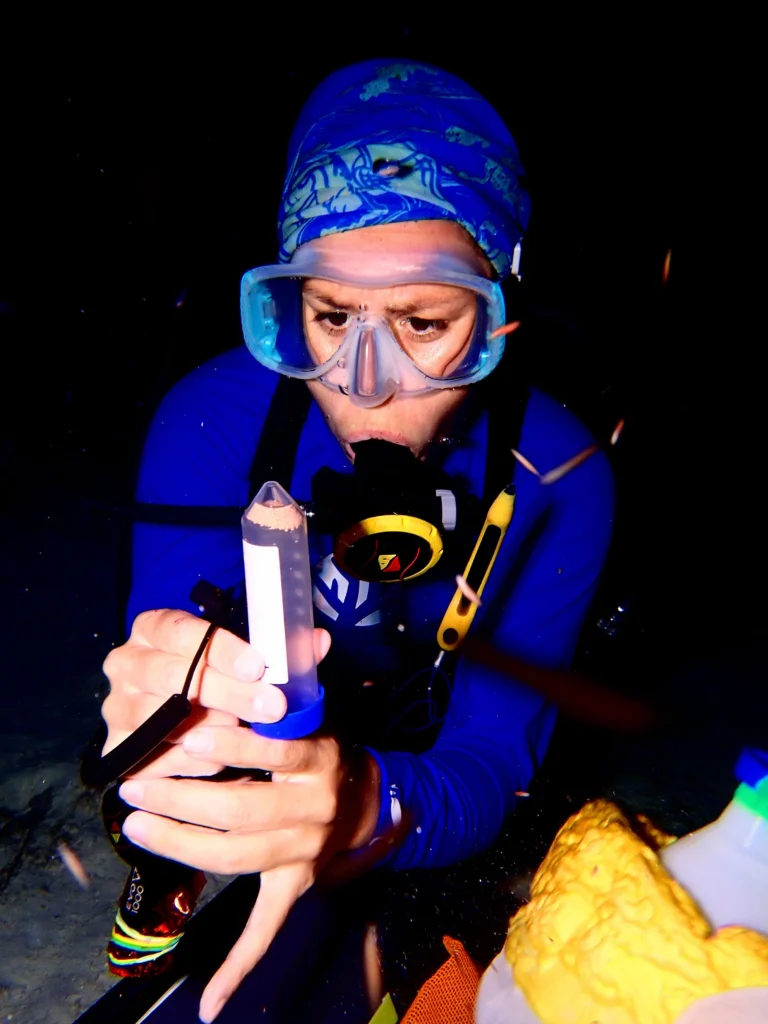

Most years, CRF™ collaborates with multiple agencies to observe and collect coral gametes during this exciting event, Witnessing restored coral colonies spawn after just a few years post-out-planting establishes that natural recovery for threatened corals is possible. A recent paper published in Frontiers of Marine Science details the findings from the last few years of spawning observations on restored reefs in a collaboration between NOAA (National Oceanographic and Atmospheric Administration), the University of Miami, and Coral Restoration Foundation™.

Nursery-raised elkhorn corals were found to spawn in sync with wild populations hundreds of miles away within just four years of being returned to the wild. Because coral restoration incorporates multiple genotypes in a smaller area than remaining wild populations, the paper concluded that there is a greater number of individuals contributing to reproductive events, likely increasing the number of viable larvae produced compared to degraded sites with less diversity. The long-term goals of reef restoration are to produce mature-sized, self-sustaining coral populations. Through spawning observations, CRF™ is closing the loop, taking corals from small fragments to mature outplanted colonies that are successfully contributing coral larvae to the next generation.

Last week our corals were observed spawning on the reef as well as in the nursery. However, this spawning event was a little different.

The corals were likely gearing up for a “split spawning” event this year in which some corals of the same species will spawn around one full moon, and others around the following full moon. Gametes that were collected and studied were found to be of varying viability this year; many were small, underdeveloped, and did not fertilize. This indicates that many of these corals may have “stress spawned” – releasing their eggs and sperm before they were fully developed in a last-ditch attempt to ensure the continuation of their DNA before they succumb to the current bleaching event.

We are still gathering data and studying the gametes. We will also be running spawning observation trips for the late August full moon. We will have more updates on the 2023 spawning season in the next issue of “Talking Science”.

Written by: Sage, “Talking Science” Content Creator