Revolutionary Coral Restoration Technique: How CRF™ Collaborates to Save Florida’s Reefs from Extinction

Corals, like all living things, have a unique genetic code, their DNA.

These are the instructions for building their functioning bodies. The differences in sections of DNA or genes within a coral result in different traits between individuals. Each individual coral is a different genotype. There are visible traits, such as hair or eye color in humans or growth forms or patterns in corals. There are also traits that are not obvious, such as poor eyesight or disease resistance.

Because Florida’s Coral Reef has lost 98% of the stony corals, there are not many unique individuals or genotypes left compared to 50 years ago. Coral Restoration Foundation™ (CRF) was able to take samples of almost all the remaining elkhorn (Acropora palmata) and staghorn (Acropora cervicornis) colonies to use for restoration, and we continue to collect samples of other species during our coral rescue projects.

We currently house over 1,300 unique genotypes across 20 different species in our gene banks. By incorporating as many different genotypes as possible into our restoration strategy, CRF™ is retaining the ecosystem’s natural resiliency in the restored population. Each genotype has different strengths and vulnerabilities, so having a variety of corals will ensure that some of them will survive through challenging conditions, such as novel coral disease outbreaks and bleaching events.

The traditional method used at CRF™ is asexual coral fragmentation. This method produces large numbers of reef-ready coral pieces; however, this does process creates clones of the parent coral, increasing population size and living coral tissue, which leads to the stabilization of a rapidly deteriorating ecosystem. To reshuffle the existing genes, sexual reproduction is needed. Luckily, the acroporid corals in the CRF™ nursery, and some outplanted corals, spawn every year in August, producing millions of potential new genotypes. CRF™ and the Florida Aquarium have worked together for the past 5 years to determine if sexually produced staghorn corals can be outplanted back to the reef after being raised in a land-based facility.

The collaboration started with scientists from the Florida Aquarium, Dr. Joseph Henry and Dr. Aaron Pilnick, visiting CRF’s Tavernier Nursery in August of 2017 and 2018. During the spawning events, gametes from staghorn corals were collected and brought back to land where they were fertilized, turning into baby coral larvae called planulae. These planulae had new variations of DNA, making them a completely unique recombination of their parents’ DNA. Both cohorts of new coral babies were settled on tile substrates and raised in a flow-through aquarium tank. The corals from 2017 spent a total of 20 months there while the corals from 2018 spent 8 months being cared for in the land-based facility. Once the corals were happily growing, they needed to be returned to the ocean. The small staghorn corals were brought to the Keys and either outplanted or held in the Tavernier Nursery to assess differences between age and time spent acclimatizing to ocean conditions.

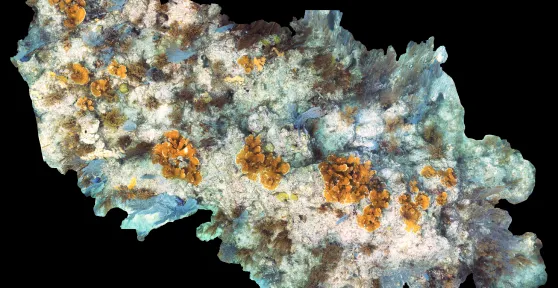

Some of the corals were outplanted at Carysfort Reef using two different methods to determine the best way to outplant smaller colonies. Another group was planted at Tennessee Reef and Cheeca Rocks along transects for the experiment. One group of corals remained in the nursery for an additional 8 months. The scientists from Florida Aquarium monitored the corals at Tennessee Reef, Cheeca Rocks, and Tavernier Nursery for 480 days (about 1 and a half years) and published the findings in the research journal, Coral Reefs. (The abstract is available here for a summary of their findings!)

Both the outplanted and nursery corals did well with 73% survivorship. The corals in the nursery did the best with 93% survivorship, proof that we care for our corals well in our open ocean nurseries. The nursery corals also grew about 40 times faster than the ones outplanted onto the reef, showing us something we mostly knew but were happy to have confirmed, Coral Tree™ nurseries support faster coral growth which allows restoration orgs to scale up their work, meeting the demand presented by the rapid decline of natural coral reef habitats.

This was the first time sexually produced corals were outplanted at Coral Restoration Foundation™ and is a huge step towards understanding genetic diversity as it relates to coral reef ecosystems and corals themselves surviving future changes and challenges.

The final chapter of this experiment is still ongoing. After approximately 1,000 days (about 2 and a half years) in the nursery, the remaining sexual recruits were outplanted to Carysfort in December 2021 with the same methodology as those at Tennessee Reef and Cheeca Rocks. (See our February 2022 Talking Science article here for details!) These corals spent a much longer time growing in the nursery and were therefore much larger than the ones outplanted previously.

In March of 2023, Dr. Joseph Henry and Dr. Aaron Pilnick returned to Carysfort with CRF’s Hayley Bedwell to monitor the sexual recruits that were outplanted on Carysfort Reef after 2.5 years in the nursery. They recorded the number of colonies still alive, took photos, and measured them with rulers underwater to determine how much they have grown since being placed on the reef. By comparing these groups of outplants, Dr. Joseph Henry and Dr. Aaron Pilnick can determine if there are significant benefits to acclimatizing land-raised corals to open-ocean conditions before outplanting.

The legacy continues as CRF™ has received more sexually produced land-reared staghorn and elkhorn corals from Florida Aquarium, further increasing the available genotypes for restoration to the biggest barrier reef in the United States. The elkhorn coral recruits have grown so large they were recently brought to our headquarters to be fragmented; each genotype now has its own branch in the nursery instead of a single fragment. As the production of these new coral individuals continues, they will be incorporated into the reef.

Hopefully, with enough diversity and massive scale restoration, the coral reefs here in Florida will stabilize and jumpstart their natural recovery processes, allowing them to survive throughout the coming global climate changes and other unexpected events. The genetic diversity within the CRF™ nurseries will give these reefs a fighting chance, and the emerging technology in restoration to use sexual propagation in conjunction with an ocean nursery phase before outplanting may assist in these large goals.

Coral Restoration Foundation™ has the infrastructure available to assist restoration science through collaborations such as this one with the Florida Aquarium, to start your own research collaboration please reach out through our email, info@coralrestoration.org.

Written by: Sage, Former CRF Intern and Madalen Howard, Former CRF Communications and Outreach Coordinator.